Singapore is known to be a racially harmonious country, but are we really?

Slightly over a week ago, we posted a video where an Indian girl shared about her experience with racism in Singapore. Hundreds of comments came in, with many Singaporeans sharing their own run-ins with racism in our country.

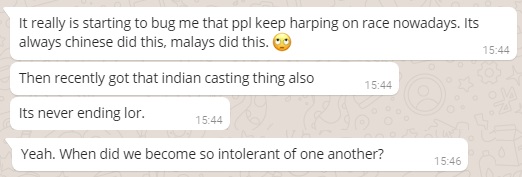

Recently, there was also a huge hoo-ha surrounding a Facebook post by local actor Shrey Bhargava, in which he expressed his disappointment and disgust over being told to perform as “a full blown Indian man” and to “make it funny” at the Ah Boys To Men 4 casting. He said the incident made him “feel like a foreigner in my own country”.

The post caught the attention of Shrey’s friends and followers, with many agreeing that minorities are often typecasted into moulds the majority has set. The post garnered even more attention when Singapore blogger Xiaxue posted her thoughts on it. She explained how “movies are chockful of stereotypes” and said Shrey should “stop being so hypersensitive and uptight”.

Many Singaporeans also took to their social media to weigh in on this whole ‘Minority VS Majority Race Thing’.

This is all worrying proof of how divided we are right now.

Take for example the Geylang Serai Ramadan Bazaar. What should have been a happy celebration over the Ramadan period has become the subject of heated racial debates.

What is happening, guys?

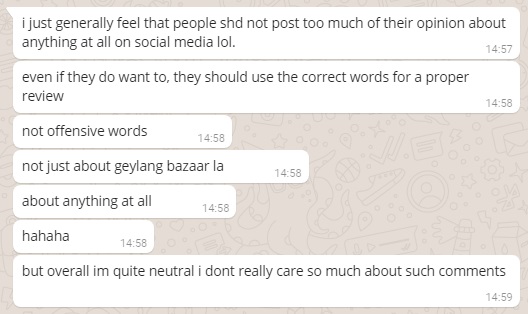

Maira: I don’t really care about such comments, but generally people should watch what they post.

We all have our own personal beliefs, but in this racially hypersensitive time, we think all of us should be more aware of what we say to one another. What do you say?

Also read People Leave, But You Don't Have To Be The One Left Behind

(Top Image Credit: theodysseyonline)

We all have our own personal beliefs, but in this racially hypersensitive time, we think all of us should be more aware of what we say to one another. What do you say?

Also read People Leave, But You Don't Have To Be The One Left Behind

(Top Image Credit: theodysseyonline)

Non-Halal Items At A Ramadan Bazaar

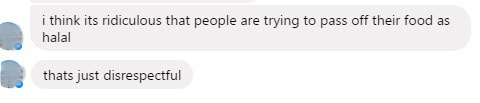

The Geylang Serai Ramadan Bazaar have been around for a long time. Spanning the entire month of Ramadan, the annual bazaar is more than a glorified festival or pasar malam. The bazaar is meant to be a celebration of the traditions and heritage of the Muslim community, tying in Muslim beliefs like giving back to the community, abstaining from anything Haram (forbidden by Islamic law), and spending time with loved ones. This year's Ramadan Bazaar boasts 1,000 F&B stalls – a large number, which had the team at The Halal Food Blog raising their eyebrows. With that, they went through the tedious effort of checking out every stall at the bazaar <a href=" suss out what’s halal and what’s not. What they found: “it seems like just around 50% of the stalls could be verified as Halal or Muslim-owned. The other half were either not Halal/Muslim-owned OR when we asked, they were not able to justify whether or not their stall was Halal.” There were stalls that put up makeshift signs that say “Halal” or “Halal Foods”. Upon probing, they were told by the stall attendants that it’s “no pork no lard”. The blog post stirred the sentiments of the Muslim community. Some find it disrespectful, because it taints the very existence of a Ramadan Bazaar – why is there non-halal food in a Ramadan Bazaar? For some, it boils down to giving basic respect to the Muslim community, whether it be by giving priority to Muslim tenants, or by being transparent about whether their food and beverages are halal or not. Conversation With A Muslim Friend Of Ours

Conversation With A Muslim Friend Of Ours

Racially Sensitive Remarks

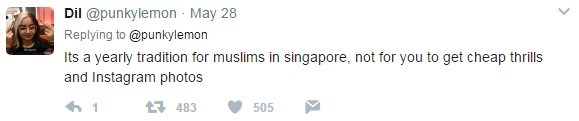

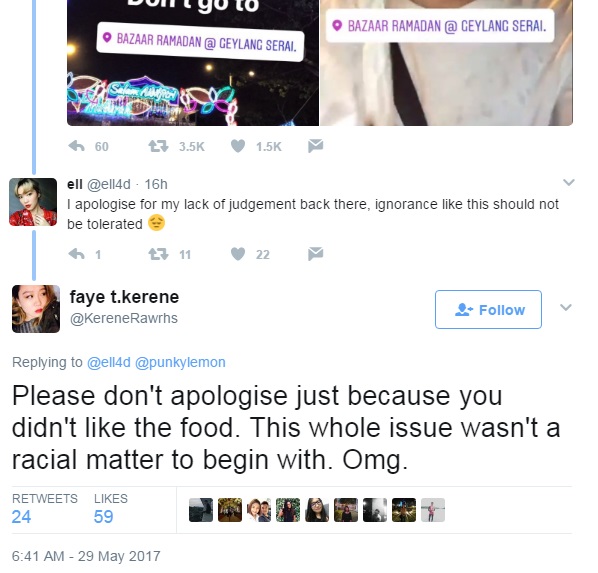

The other issue plaguing the bazaar is even more troubling as it touches on issues of Chinese privilege and of Malays being a minority. It all started when local influencer Ellie posted Instagram Stories about the bazaar with captions like “Food sucked. Don’t go to (the Ramadan Bazaar)”, and “Sucked Balls”. Twitter user Dil (@punkylemon) responded with screen captures of these IG Stories, coupled with a tweet saying “What makes you think the ramadan bazaar is for your privileged chinese ass.” Image captured from @punkylemon’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @punkylemon’s Twitter profile

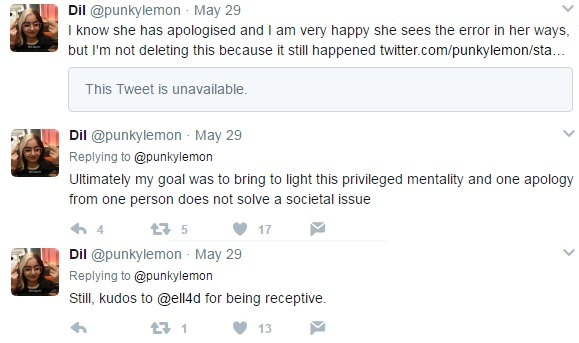

Images captured from @punkylemon’s Twitter profile

Images captured from @punkylemon’s Twitter profile

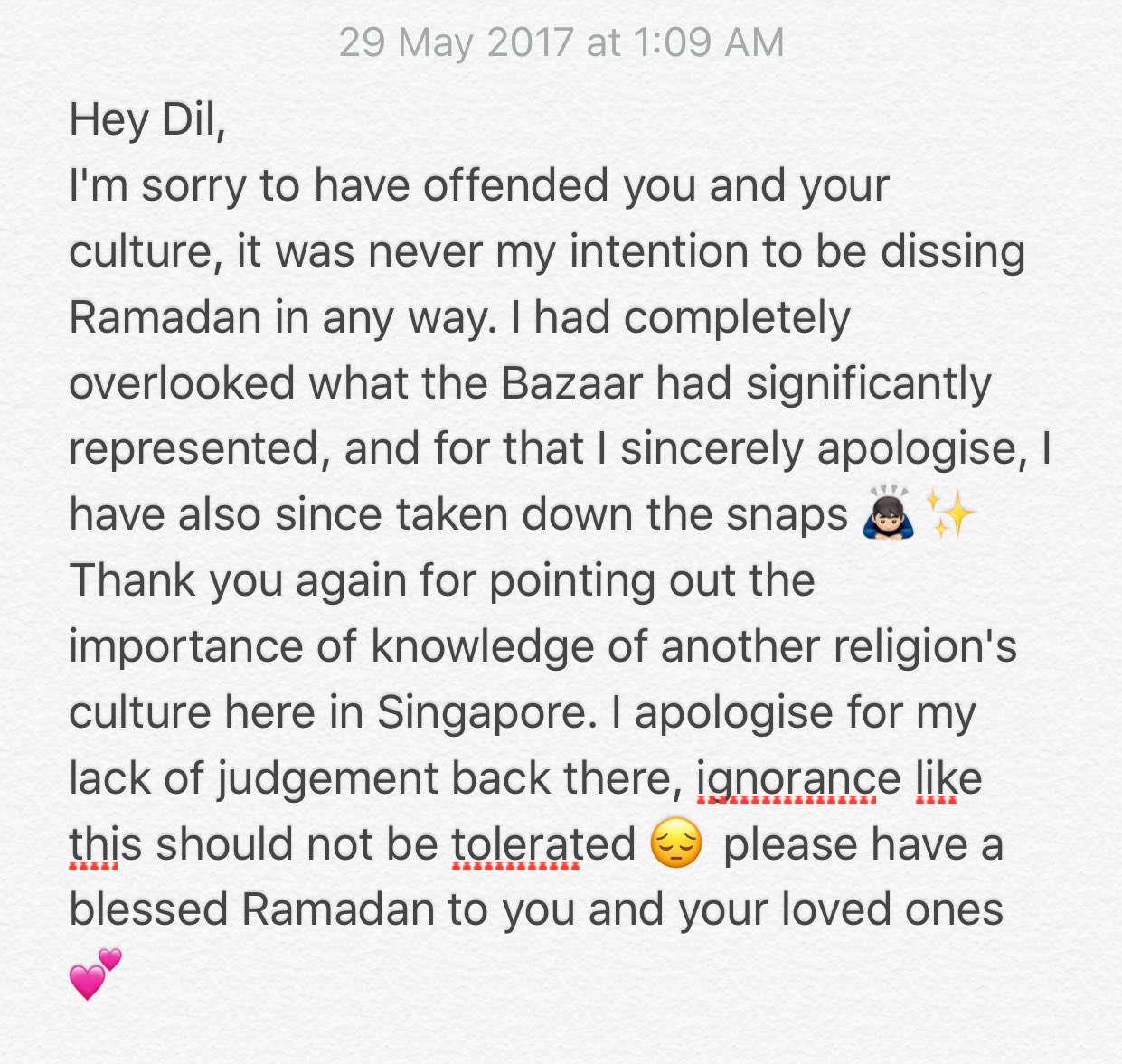

Image Credit: @ell4d’s Twitter profile

Image Credit: @ell4d’s Twitter profile

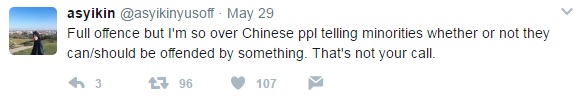

Image captured from @asyikinyusoff’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @asyikinyusoff’s Twitter profile

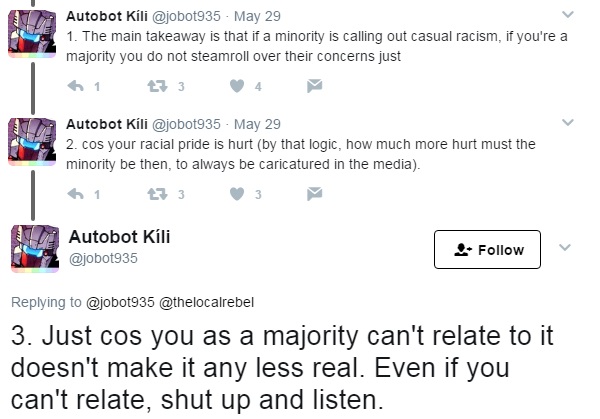

Image captured from @jobot935’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @jobot935’s Twitter profile

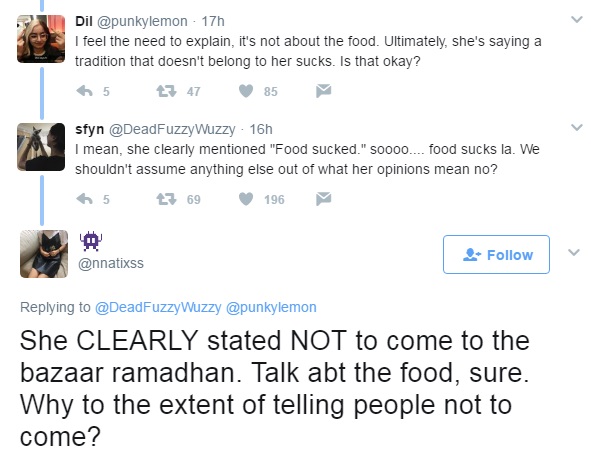

Image captured from @punkylemon’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @punkylemon’s Twitter profile

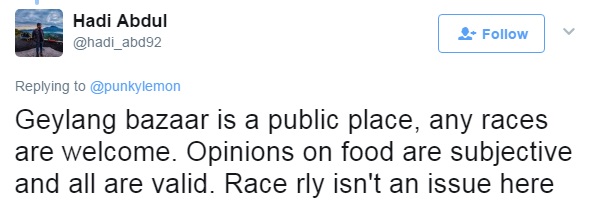

Image captured from @hadi_abd92’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @hadi_abd92’s Twitter profile

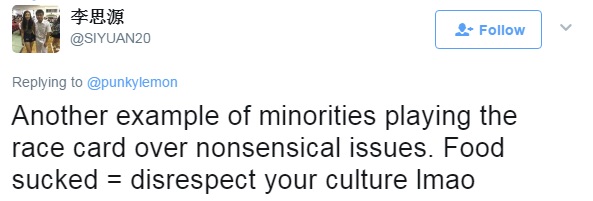

Image captured from @SIYUAN20’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @KereneRawrhs’s Twitter profile

Image captured from @KereneRawrhs’s Twitter profile

What’s wrong? What’s right?

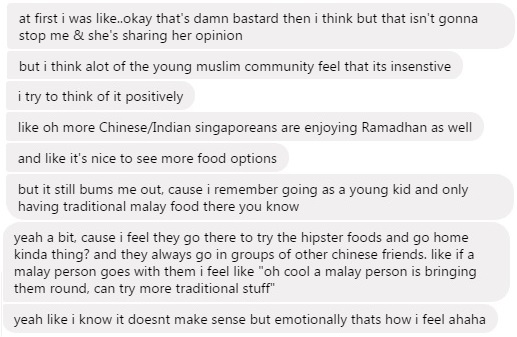

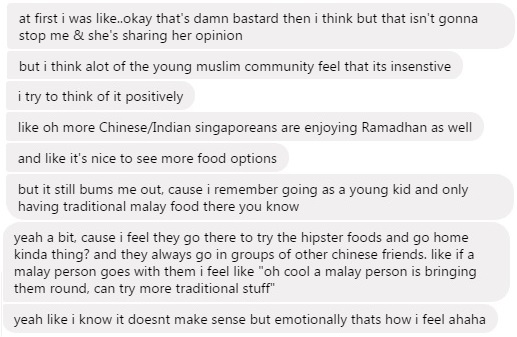

Is the bazaar getting too commercialised for its own good? Now that more non-Muslims are flocking to the bazaar for the food and festival vibe, are Muslims bothered by it? As a Muslim in Singapore, how affected are you when non-Muslim Singaporeans make remarks like those mentioned above? Instead of deciding for ourselves, we asked our Muslim friends and here are their thoughts.Natasha: I think it’s insensitive to make such remarks but I try to think of it positively.

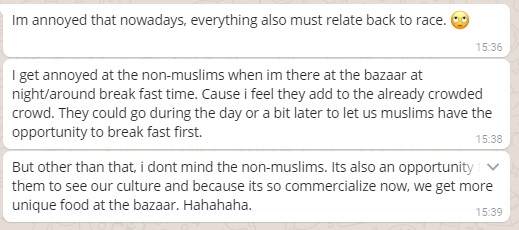

Ain: I do get annoyed, but when did we become so intolerant of one another?

Maira: I don’t really care about such comments, but generally people should watch what they post.

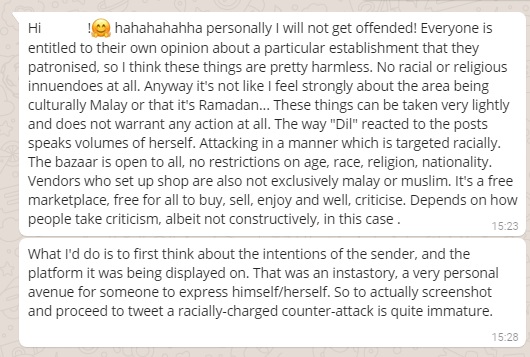

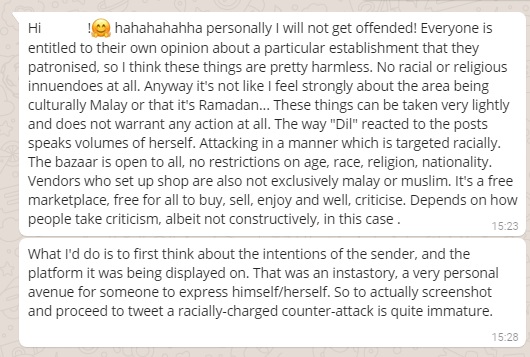

Siti: I’m not offended, everyone is entitled to their opinion.

We all have our own personal beliefs, but in this racially hypersensitive time, we think all of us should be more aware of what we say to one another. What do you say?

Also read People Leave, But You Don't Have To Be The One Left Behind

(Top Image Credit: theodysseyonline)

We all have our own personal beliefs, but in this racially hypersensitive time, we think all of us should be more aware of what we say to one another. What do you say?

Also read People Leave, But You Don't Have To Be The One Left Behind

(Top Image Credit: theodysseyonline)I was born Muslim. I grew up in a Muslim family. While my parents weren’t the most religious of people, my upbringing was very much Muslim. I went for Friday prayers at the neighbourhood mosques, was taught to read the Quran, and would visit the mosque during Hari Raya Puasa and Haji. As a young boy, I went to religious classes every Sunday morning, where we would learn about the different aspects of the religion- it’s history, the five pillars and how to speak Arabic. I attended all my religious classes diligently and even got a certification of completion by the end of it.

Religion for me at the time wasn’t so much about belief as it was about following my parents, because that’s just how it is. You follow the religion of your parents, because they’re your parents and you’re just a child. I did as I was told; No more, no less.